Editorial note: Yeah, I’m uncomfortable with the name of the film, particularly since I’m a white dude.

I recently watched The American Society Of Magical Negroes. I enjoyed the film, though clearly I’m not the primary audience. But I kept wondering who, exactly, was.

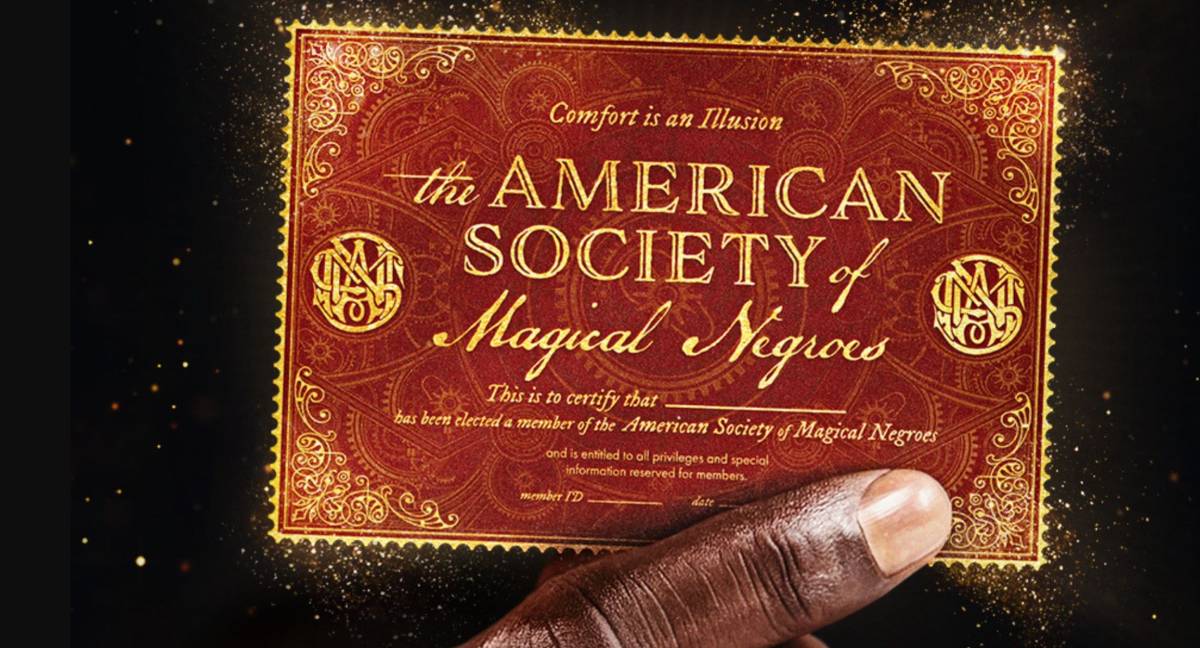

The premise is laid out pretty clearly in the trailers — there is a secret society of Black people, with magic, whose sole "world-saving" mission is to avoid white people being uncomfortable. Justice Smith plays a struggling artist who is recruited into this fantastical society.

There’s little surprising in this film and a lot that is perhaps a little too on the nose; a techbro CEO mentions bidding on a first edition of The Fountainhead. But that’s the danger of having your central conceit being "what if the horribly stereotypical and racist trope of the Magical Negro was real?"

In the film, the society explicitly is not just about advancing the "plot" of their white clients, but also ensuring that they never feel too uncomfortable… because when white people get uncomfortable, Bad Things Happen. {1}

Black appeasement of white sensibilities to avoid harm is a very real thing — as is its failure to achieve anything like equity. For example, research looking at racial inequities in US healthcare found them literally everywhere, yes, including the places that you’d think would be doing better.

So the plot arc and moral of the film is telegraphed heavily: What you give up to appease someone else’s sensibilities ends up diminishing yourself. Honest communication, although uncomfortable, is the only way to reach our common humanity and be able to move forward.

While this makes the film unsurprising, it’s also the most interesting part of the film. Arguments about not just if to protest, but how to protest, are nothing new. However, the film’s characters articulately make their arguments for all sides, showcasing their strengths and (sometimes ridiculous) weaknesses. Seeing them all articulated well in a row was definitely a worthwhile experience for me.

But that brings us back to whom this film was for.

Those who need to watch this film almost certainly won’t. Everyone who would be open to watching this film — such as myself — is likely already on board with its eventual conclusion. And a monologue Justice Smith delivers (quite well) at the climax of the film explains why, perhaps, a sizeable number of people tuned right out:

You’re not my friend. And you don’t want to be friends, because if we were actual friends, you would have to talk to me and listen to me and make space for the reality that I live in a country that makes me feel like it wants me dead. Where if I get shot today, there is an army of people ready to explain how it was probably my fault. And I feel that every day.

Yeah, because that’s a real thing. And it’s something that I can only imagine that a lot of Black people in the US really don’t need a reminder of.

So who is this film for?

There are an array of Black actors that have cameos and smaller roles. I’m willing to guess that nearly every last one of them loved being able to say the quiet parts out loud, on film.

I can only imagine how glorious that felt.

{1} An end credits scene (plus a line of dialogue) nods to the fact that this kind of appeasement is also a fact of life for women as well.