There are rules to every disagreement.

Every argument, every debate, every philosophical discussion, every “my team is better than your team” drunken shoutfest – they all have a set of unwritten rules.

But those rules can be hijacked. If one side is operating in bad faith, it’s fairly easy to create arguments that look like they should be right… but aren’t.

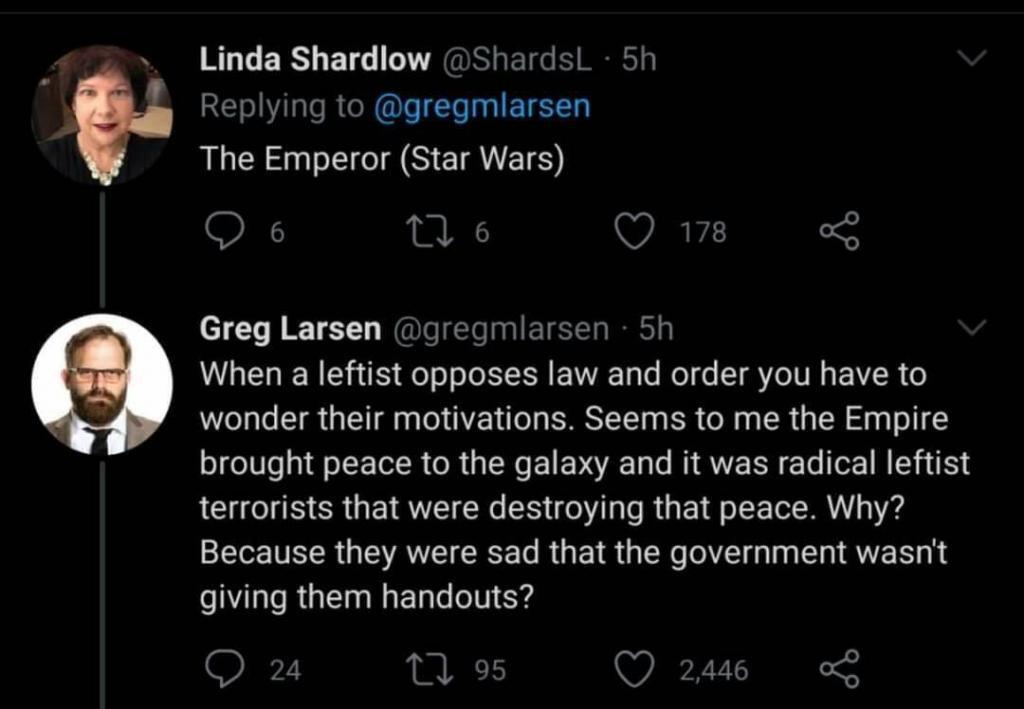

A gentleman named Greg Larsen went through and showed exactly how that works. He challenged folks to “[n]ame someone who is universally agreed to be evil (genocial dictator, serial killer etc) and [he’d] defend them and their actions using conservative logic.”

And then he proceeded to do so. In a series of tweets, he defended Hannibal Lecter, Hitler (of course), Jack the Ripper, Emperor Palpatine, Osama bin Laden, Kim Jong Un, the Borg, and more. It’s worth looking at the screencaps on imgur: https://imgur.com/gallery/nNcx7LE

The shape of these arguments is perfectly reasonable. They seem like they should be correct… but we know that they aren’t.

There are two ways to deal with this kind of bad faith argument.

The first is to be able to discern the difference between the shape of the argument, and the content. With the examples from Mr. Larsen, the distinction is fairly easy to see. In real time, and especially when it’s said out loud, it can be hard to spot sometimes.

The second – and much better – way is even simpler.

You don’t argue to win. You argue to reach consensus. To reach understanding. To be able to work together.

When you argue that way – about reaching solutions instead of ensuring one team “wins” – it is very difficult for the bad faith actors to operate. The content of their argument – rather than the shape of it – matters. And if you’re operating in bad faith, it all falls apart.

Featured Photo by Geron Dison on Unsplash