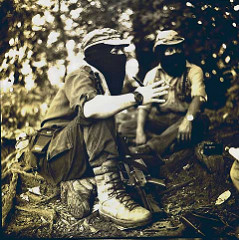

Radicalism doesn’t necessarily come from the intensity or degree of one’s beliefs. It comes from a lack of faith in others. It comes from a feeling of being ignored and unable to participate in the process. It comes from being excluded.

Radicalism doesn’t necessarily come from the intensity or degree of one’s beliefs. It comes from a lack of faith in others. It comes from a feeling of being ignored and unable to participate in the process. It comes from being excluded.

This seems simple to solve. This isn’t exactly a new hypothesis – if the end to radicalism is so obvious, then we should have done it already and entered into an era of peace and love and happy singing birds (or singing dinosaurs, depending on your preferences).

Conflict theory claims that the persistence of radicalism and violence is because those in power do not wish to give it up. That’s certainly true in many cases. When parents are bossed around by children, we disapprove of it so strongly that we make reality TV shows out of it, where an English nanny or a somewhat smarmy psychiatrist administers advice on daytime TV.

But that’s not all cases. The remainder are, surprisingly, easily explained as well.

Ideology has a strong influence here. A rigid, uncompromising view means that one’s odds of getting what you want are substantially lower. But those with a relatively moderate ideology can still become radicalized – and it’s because they *don’t believe* they’re being heard.

I’ve seen managers make overtures to workers – and be greeted with distrust and anger. It’s not because of the managers’ self-perception; at those times they may be truly wishing to cede some power and authority in return for teamwork. The perception is in the workers. Regardless of what management says, the workers do not *see* trust – they see just another ploy. Rather than work with the system, rather than talk, they’d rather strike, grumble, sabotage, or just plain complain.

This principle scales. The more one thinks they can influence others (whether through votes, words, whatever), the less likely they are to try violence. The less one believes they can actually participate in the system, the more likely they are to go outside the system. It’s true that sometimes, with some people, it is impossible to bridge that gap. But to presume that entire groups, entire swaths of people are unable to be reasoned with… that’s our shortcoming, not theirs.

The challenge for us with privilege is twofold: Both to hear those who are willing to work with us, and to remember that the burden of proof – the evidence that we *are* really listening this time – is not on them… but on us.