I’m having a hard time writing anything for here, simply because it seems so self-evident. For example, I’ve been thinking about how we conceptualize things in words (inspired by Dorothy Smith:

It’s not just what you say, it’s how you say it. It’s how you think it, which reflects how you conceptualize it. Too frequently, this means that once you’ve locked into a model of something – ANY model – then you’ve accepted its limitations. It’s limitations in appraising reality, that is. Reality’s limitations aren’t a function of your conceptualization. Obviously, you’d want to use a conceptualization with as few limitations as possible.

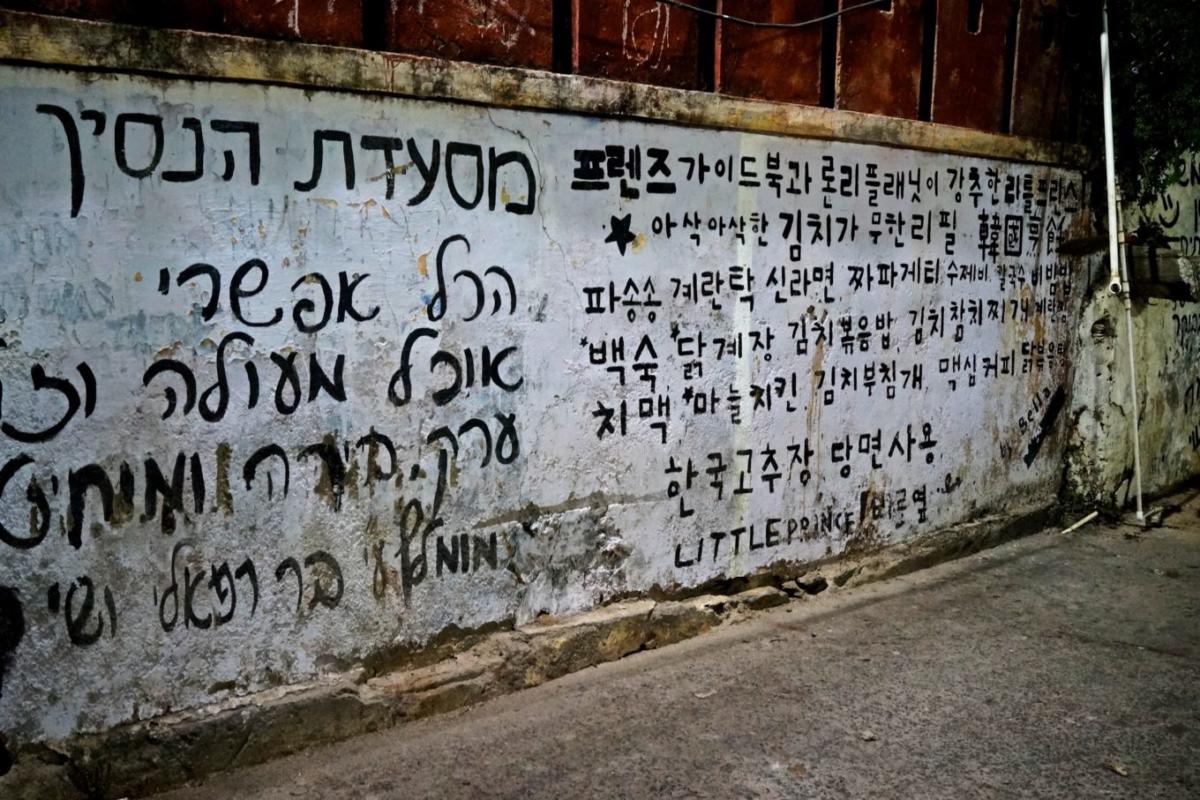

Yet *all* conceptualizations have limitations. It’s like languages – each language has its own concepts that are effectively untranslatable. Even routine translations are frequently “lossy”; the information of nuance disappears. The obvious solution to that problem is to become multilingual. The obvious solution to our conceptual problem is to recognize the modeling nature of our conceptualizations.

I do assert that there is an empirical reality, that it’s not just some “idealized” Platonic form, but there’s a physical reality out there external to the observer. However, our conceptualization (even in the supposedly empirical sciences) has limitations. Understanding that these limitations exist can signal us when it is time to switch to a different conceptualization in order to bring ourselves to a close understanding of our external reality.

The other month, my wife and I were trying to discuss a quality of “being” – someone *is* X, Y, and Z. We were at a sticking point until I said – “Not ser, estar!”. The two types of “is” in Spanish carry extra information that simply isn’t there in English. Running against that limitation clued us in that it was time to switch languages briefly, and then we merrily went on in English again.

So this brings us to modeling – not an methodology, really, but a meta-methodology. An understanding that “you use a model that brings you closest to reality until it doesn’t – then you use a different model.” This sensibility is peculiar to us in this time. The positivists missed it in their assurances that they were right, the postmodernists missed it in their assurances that everything was relative and mutable. This way – a non-synthesizing synthesis of what has come before – may allow us to take the best of the past and move boldly into the future.

… Okay, so that’s a little more than I thought it would be at first. Still, it’s self-evident, right? If history is any judge, I’ve just written about (and conceived) something that another has already described ad nauseaum elsewhere, and I just haven’t heard about it yet. Do let me know if this is the case.